Introduction

The human eye, often referred to as the "window to the soul," is a sophisticated organ that plays a fundamental role in our perception of the world. Its complex anatomical and physiological attributes have intrigued both modern scientists and traditional healers for centuries. While contemporary ophthalmology meticulously analyzes the eye's structural and functional components, Ayurveda—the ancient Indian system of medicine—interprets it holistically as Netra Sharira (eye anatomy), integrating physical, physiological, and energetic dimensions. This article offers a comprehensive examination of the eye’s intricate structure and its function by merging modern scientific insights with Ayurvedic wisdom, fostering a more profound understanding of this remarkable organ.

Structure

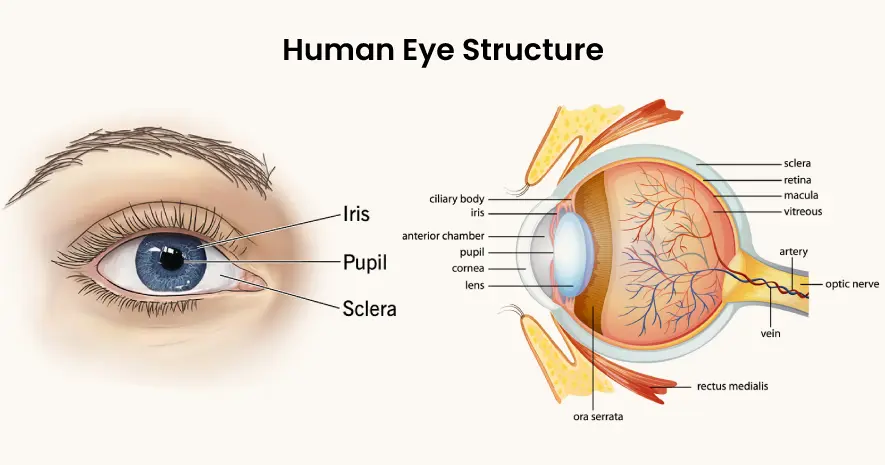

The eye is a highly specialized organ designed for capturing, processing, and transmitting visual information. From an anatomical perspective, it comprises multiple layers and chambers, each serving a distinct role in vision.

The external layer consists of the sclera and cornea. The sclera, a dense, fibrous structure, provides mechanical protection and maintains the eye’s shape. The cornea, a transparent, avascular tissue, serves as the primary refractive surface, bending incoming light to initiate the focusing process.

The intermediate layer includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. The iris, a pigmented muscular structure, regulates light entry by modulating pupil diameter. The ciliary body, responsible for aqueous humor production and lens accommodation, enables dynamic focusing. The choroid, a vascularized layer, supplies oxygen and nutrients to the retina, playing a crucial role in ocular metabolism.

The internal layer is the retina, a highly specialized neural tissue containing photoreceptor cells—rods and cones. Rods function in low-light conditions, facilitating scotopic vision, while cones mediate color perception and high-acuity vision under photopic conditions. Retinal processing converts light stimuli into electrical impulses, which are transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve.

In addition to these layers, the eye comprises three fluid-filled chambers: the anterior chamber (between the cornea and iris), posterior chamber (between the iris and lens), and vitreous chamber (between the lens and retina). These chambers contain aqueous and vitreous humor, which contribute to intraocular pressure maintenance, optical clarity, and metabolic exchange.

From an Ayurvedic perspective, the eye’s structural components are classified into distinct mandalas (circular regions): Pakshma Mandala (eyelashes), Vartma Mandala (eyelids), Shukla Mandala (sclera and conjunctiva), Krishna Mandala (cornea and iris), and Drushti Mandala (pupil, lens, and retina). These classifications emphasize not only structural attributes but also functional and protective roles, aligning with the holistic nature of Ayurvedic science.

Visual Processing

Vision is a highly coordinated process involving optical refraction, neural transduction, and cortical interpretation. Light enters the eye through the cornea, where it undergoes primary refraction. The iris dynamically adjusts the pupil’s aperture to regulate the intensity of light reaching the lens, which further fine-tunes focus through its accommodation mechanism. The focused image is projected onto the retina, where photoreceptors initiate the conversion of light energy into neural signals.

These signals propagate through the retinal layers to the optic nerve, which transmits visual information to the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus and subsequently to the visual cortex for higher-order processing. This cascade enables the perception of depth, motion, contrast, and color, forming the rich visual experiences that define human perception.

In Ayurvedic philosophy, this process is conceptualized as Rupa Grahana (perception of form), which extends beyond the physiological mechanism to encompass cognitive and environmental interactions. The Drushti Mandala is recognized as the focal region where light perception occurs, linking vision to the Panchamahabhutas (five elemental forces) and the Tridoshas (biological humors). The equilibrium of Vata, Pitta, and Kapha is considered essential for maintaining optimal ocular function, and imbalances are associated with specific visual impairments.

The human eye is an extraordinary organ that exemplifies the synergy between structural precision and functional sophistication. While modern ophthalmology provides a detailed account of its anatomical complexity and physiological mechanisms, Ayurveda offers a holistic framework that integrates structural integrity with energetic balance. By harmonizing these perspectives, a deeper appreciation of ocular health emerges—one that acknowledges both the scientific rigor of contemporary medicine and the integrative wisdom of Ayurveda. Understanding the eye through this dual lens fosters a more comprehensive approach to vision care, enriching both clinical practice and holistic wellness

March 05, 2026

February 11, 2026

February 11, 2026

January 29, 2026

January 23, 2026

January 12, 2026

We use cookies that are necessary for the smooth operation of the website, to improve our website and to display advertising relevant to you on social media platforms and partner websites. By clicking "Accept all", you agree to the use of cookies for convenience features and statistics and tracking. You can change these settings again at any time. If you do not agree, we will limit ourselves to technically necessary cookies. For more information, please see our privacy policy .